What Clinicians Really Think About AI

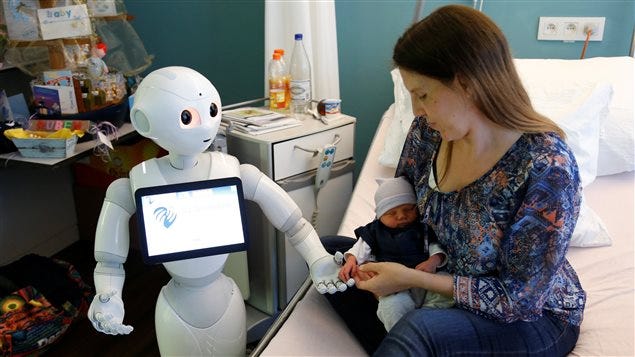

Recent Past: Technology in Healthcare Doesn’t Live Up to the Hype 🩺

Hello Everyone,

A lot of my readers ask about A.I. in healthcare or education when they respond to my welcome Email, so I’m especially on the lookout for guest contributors in those domains.

As more Physicians become more familiarized with Generative A.I. and new technology in the workplace and A.I.’s impact in research, I was looking for someone who ha…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to AI Supremacy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.